Transitional justice: SC hears case on Nepal’s need to ratify Rome Statute

Kathmandu, November 14 — On Thursday, a single bench of the Supreme Court, led by Justice Manoj Sharma, convened to hear a case. Advocate Rabindra Tamang stood up to present his arguments and began by saying, “Sir, the Rome Statute was created by the United States. They have not ratified it, but we must."

Advocate Tamang then shifted his discussion to the European Union (EU), saying, “The US provides weapons and projects, but the EU also offers humanitarian aid. So, should we lean towards the US or the EU?”

Answering his own question, Tamang explained, “The US is a development partner for Nepal, and it trades weapons globally. The EU has provided significant humanitarian assistance to Nepal. However, we must remain neutral and not take sides with any country. Remaining neutral doesn’t mean we excuse crimes.”

This was part of his argument for why Nepal should ratify the Rome Statute. He pointed out that despite repeated requests from Prime Ministers, ministers, and past governments to pass the Rome Statute, it had not been ratified yet.

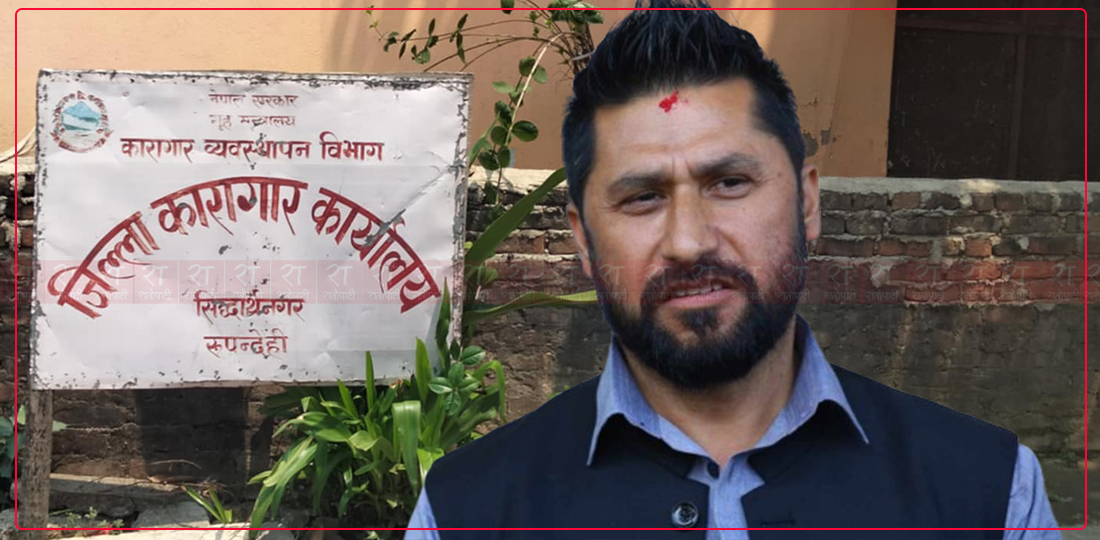

The writ petition was filed by Advocate Tamang and Advocate Chiranjivi Nepal, naming the President’s office and seven other institutions as defendants. In the preliminary hearing, Justice Sharma asked them to stay focused on the subject, questioning, “What exactly are you requesting in the writ, and what order should the bench issue?”

Tamang continued discussing the necessity of the Rome Statute and whether Nepal should become a member state. He highlighted that the process of transitional justice in Nepal had been delayed for a long time, leaving victims without justice. He argued that the Rome Statute would offer a path for international courts to intervene in such cases.

Tamang further explained that the Rome Statute, which established the International Criminal Court (ICC), was adopted on July 17, 1998, and came into effect after four years (July 1, 2002). As of today, 124 nations have ratified it, while 30 countries had signed it but not ratified it. He emphasized that Nepal should be among the nations that ratify the statute.

He explained that the Rome Statute aims to hold accountable anyone involved in genocide or crimes against humanity, even if the state itself cannot or will not prosecute the offenders. He argued that for Nepal’s victims, the Rome Statute would open up avenues for international justice, particularly in cases where justice has not been served domestically, like the Chitwan Madi incident during the conflict.

Tamang demanded that the court issue a show-cause order and request a written response from the government. He argued that criminals from Nepal's conflict period should be subject to both national and international judicial scrutiny, and the country should ensure that international judicial access is available.

The Rome Statute's Article 5 provides for the prosecution of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, regardless of where they are committed. If a state is unable or unwilling to prosecute such crimes, the International Criminal Court can step in. But for this to happen, the state must first ratify the Rome Statute.

International precedents

Tamang cited international precedents, such as the trial of former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic for crimes against humanity, and the cases involving Serbian generals and warlord Joseph Kony of Uganda, to show how the Rome Statute has been applied globally.

He also pointed out that temporary tribunals can be established under the UN to try perpetrators of crimes, citing examples like the Sierra Leone Special Court in 2002 and the Rwanda Tribunal in 1994.

In conclusion, Advocate Tamang urged the court to direct the government to ratify the Rome Statute, so that victims in Nepal can seek international justice when domestic mechanisms fail.

Leave Comment