Sacred struggles: The fight for Mukkumlung's soul

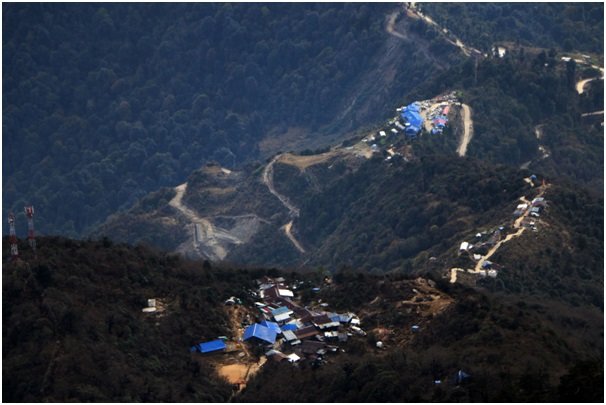

Perched atop of a sacred hill amidst dense Rhododendron Forest, the Pathibhara Temple holds deep significance for the Hindus as well as Buddhists. Indigenous Limbu and Rai communities have lived in and around the place as a conservationist for generations, holding a deep connection to the land, forests, and wildlife. But now, they fear that the cable car construction will not only disrupt their way of life but also lead to a loss of their identity and livelihood.

Although the resistance was centered around the destruction of the local forest after IME Group, the developer of the cable car, felled around 4,000 trees, under the protection of the Armed Police Force, initially, No Cable Car movement organised by the Mukkumlung Joint Struggle Committee have intensified with the frequent protests by the indigenous community, who argue that it only benefits the investors and not the locals.

The recent clash on Saturday at Baludanda left several from protestors and police injured. While political parties have urged for the expedition of the cable car construction, the Committee has been arguing that the construction of the cable car would severely impact the sacred religious site, as well as local natural resources, environment, and ecology.

IME Group has said that they will prioritise hiring local workers and ensure that many of the people currently working as porters would transition into new roles. Despite that, indigenous activists see this as one of the examples of threats to their existence and livelihood. They are in trepidation that the implementation of cable car project would irreversibly alter the region’s heritage and ecological balance.

The cable car project, which is said to have been initiated to facilitate easier access for devotees, connects the temple to the lowlands below and boost tourism, raises crucial questions about the rights of indigenous communities in the area.

In line with its international commitments under ILO Convention 169 and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), Constitution of Nepal 2015, Articles 32(3) and 51(j)8 guarantees the inclusion of indigenous nationalities in decisions concerning their communities while also ensuring their rights to protect and promote their identity, tradition and culture through special provisions for opportunities and benefits.

The construction project, without proper consultation and approval with the affected group, does not only undermine their ability to protect and preserve their cultural heritage and natural environment, but a clear violation of international norms.

Like many other cable car and hydropower projects that have been implemented in the past without following the principle of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) of the communities affected, this is another stark example of the kind of threats indigenous peoples in Nepal face, where development often comes at the expense of their identity, heritage, and the environment.

Given this, the protest against Pathibhara cable car project is a direct response to the series of violations of indigenous rights and should be understood that indigenous communities are not against development projects, rather the state should sensitise stakeholders on broader concern regarding the preservation of cultural identity and the safeguarding of Nepal’s ecological heritage.

The company drools over the fact that upon project completion after 15 months, the number of visitors to Pathivara Devi Temple might reach up to 10 lakhs. However, they seem wilful blind to be deliberately ignoring the potential risks that mass tourism might bring. The region surrounding Pathivara Temple does not have the capacity for handling such large numbers of tourists, and the construction of the cable car would likely exacerbate increased foot traffic, littering, and already existing waste disposal challenges, significantly eroding the area’s pristine beauty and biodiversity.

Furthermore, the commercialisation of the holy shrine and its surrounding would dilute the spiritual significance of the place, leading to a situation where the luxury of tourists and business gain will be prioritised over the spirituality and needs of local population. Besides cultural implications, the proposed cable car route passes through ecologically sensitive areas cutting dense forests that are home to numerous species of flora and fauna, major being the rhododendron and red pandas.

Let’s not go far, in numerous pilgrimage sites across India, traditional methods of transportation such as palanquins, ponies, and porters have been managed systematically, carefully preserved, and promoted in lieu of large-scale commercial projects. These methods may not be as lucrative, but are seen to have playing an integral role in maintaining local livelihoods, environmental conservation, and the spiritual essence of these regions.

Therefore, state should understand that the Mukkumlung protests, ongoing opposition, and the frequent strikes being called underscores their commitment to protect the future of their land, and it is vital that their demand of putting a ban on project should be recognised.

Rather than commonly promoted models of development like ‘towere’ or ‘cable car bikas’, working towards a sustainable approach that honours both the people and the land of Mukkumlung, such as improved road till Kaflepati from Suketar airport, provision of safe drinking water, health and electricity facility for the entire area should be welcomed.

The protests for indigenous rights deserve support not just from indigenous communities but also from non-indigenous groups because the future of Mukkumlung should not be handed over to the commercial forces that seek to exploit its resources.

Never-ending push for business-driven motives in every conceivable space, with little regard for environmental cost and altering of livelihoods of the people depending on the very landscapes would lead to the environmental erosion as well as deprivation of cultural and economic rights of indigenous people.

(Nabina Sapkota is a researcher at Social Science Baha in Kathmandu and is currently pursuing an MPhil in Social Work at Tribhuvan University.)

Leave Comment