Enhancing capabilities of disaster-prone communities for effective disaster prevention and preparedness

It is essential that we feel urgency for disaster prevention and preparedness to reduce the potential loss of lives, injuries and property while keeping individuals resilient to withstand the plights in disaster-prone communities sitting in hills and low-lands where rain-hazards are invariably recurrent phenomena.

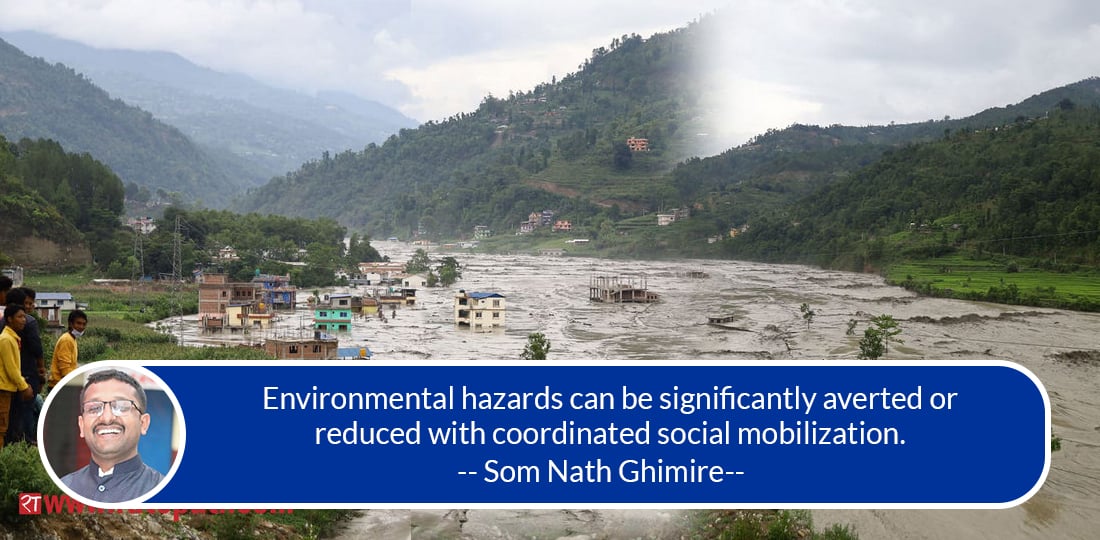

It is predictable that a spell of monsoon-triggered disasters slam Nepal every year and claim hundreds of lives and property worth million rupees. Besides, days of pounding rains cause common monsoon disasters such as landslides, mudslides, lightning, flash floods, and inundations among others which wreaks havoc on various critical infrastructures, deluging human settlements in perils. Also in many instances human settlements remain unreached by humanitarian assistance for days, weeks or even for months. As per the data maintained by the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority, last year alone between April and October, the nation recorded as many as 463 deaths caused by monsoon-induced hazards—the biggest single-year casualty since the devastating earthquake of 2015—while at least 803 people were injured, 101 others went missing along with loss of property to the tune of Rs. 797.5 million.

Although disaster preparedness and disaster management mechanisms have long been one of the key agenda of the government in coordination with intragovernmental, international partners and local agencies, the disaster risks mitigation policies have largely remained ineffective when it comes to building disaster resilient capabilities of the vulnerable communities. When natural hazards such as earthquake, avalanche, wind storms, typhoon, lightning, landslides, floods and inundation hit the human settlements, there are always the most pressing threats for societies in any nation in terms of possible loss of lives, economic setback, and socio-cultural effects including adverse psycho-social consequences. Yet, regarding common monsoon-triggered hazards like landslides in the geographical contiguity of fragile hills and mountains as well as floods in the vicinity of societies sitting on the river banks are always foreseeable in most cases. It is in this regard, we desperately need to understand the fact that some communities are more susceptible to disaster-hazards than others and act accordingly to reduce the disaster mayhem.

Environmental hazards can be significantly averted or reduced with coordinated social mobilization. True, unless vulnerable human settlements are resilient, they cannot act proactively. This is why we need to ensure optimum community participation approaches that enable the societies to come forward with efficient initiatives and civic leadership to engage the communities in prevention efforts as well as forge strong relationships to build trust for collaboration and partnership to reduce the disaster impacts during the crisis. Indeed, such collaborations and partnership efforts are paramount to tailoring strength for all the disaster cycle—prevention, response, rescue, relief and recovery assistance to the needy population as well as addressing major challenges such as gulfs in information dissemination, services and resource deliveries during the catastrophes.

Most distressingly, we have hugely failed to foster the capacities of communities to come forward with meaningful, deliberate and collective actions both to save the communities from such disastrous phenomena and impacts and reduce long term consequences. Also, the government has given little priority to increasing the understanding of the risks of the hazard-prone communities and enhancing their capabilities to mitigate the disaster mayhem.

Nepal, which is sitting along the 11th seismically active tectonic plate, is one of the world’s most disaster-prone nations. Due to the topographical fragility of its steep slopes and young Himalayas as well as frenzy streams and rivers during rainy days, human settlements in their contiguity are highly vulnerable to recurrent monsoon hazards. What is clear is that the mountainous districts sitting in the Siwalik, Mahabharat range, Mid-land as well as higher Himalayas are more prone to landslides due to their topographical vulnerability and weak ecosystem while human settlements within the basin of snow-fed perennial rivers such as Koshi, Narayani, Karnali, and Mahakali among other southern rivers are always at higher risks of being deluged. Moreover, such hazards have been exacerbated by impacts of climate change, mindless deforestation, use of heavy equipment for the rampant mining in the Chure, dearth of sustained engineering for road construction particularly in the hills and high hills. Further, they can be equally attributed to weak implementation of budgets allocated for disaster preparedness, dams, embankments and border structures constructed by India as well as lack of diplomatic acumen at home to resolve the issue with India through diplomatic talks. Similarly, given the increased density of population, certain communities or marginalized groups are more likely to be hit by the disasters as they are always forced to settle in areas susceptible to the impacts of raging rivers while no best land is left for them in the country for farming and housing. Also, due to the lack of sustained human settlement patterns and rigid land use policy as well as non-action on the part of the state agencies to respond with long-term relocation plans for disaster-hit communities, they are forced to hastily rebuild weak shelters in the very territory where catastrophes normally hit. Needless to say, this only spares vulnerable communities to be either shattered by another year’s monsoon calamities or displaced from indigenous habitats.

The scale of each disaster, whether it is relating to loss of lives, damage of property or socio-cultural capacity, has long-standing repercussions for marginalized populations while they are left with almost no measure of physical and economic safety for the future. Also, the deaths, severe injuries and potential scarcity of foodstuffs continue to functionally weaken the communities for months whereas the possible outbreak of communicable disease continues to impact the societies.

As most of the vulnerable communities belong to rural areas and the impacts they go through in the aftermath of disasters are different than that of the communities belonging to urban areas, it is critical to assess how disaster vulnerabilities impact societies and intervene accordingly to reduce the disaster consequences.

Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (DRRM) Act (2017) has made it statutory for the National Disaster Risk Reduction Management Authority (NDRRMA) to coordinate with tiers of government to prepare annual reports on disaster risks and mitigation efforts with bottom up approach. As per the rules, NDRRMA is the apex agency under the Home Ministry to implement national policies on disaster risks mitigation approaches across the nation both to prevent and tackle the crisis in the aftermath of disasters. NDRRMA is required to work closely with the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology and Department of Mines and Geology to disseminate early alert messages to the hazard prone communities.

The disaster prone communities, however, are left in ruins during disasters owing to long-existing coordination and communication gaps among intra-governmental, non-governmental and private humanitarian agencies at all levels. This is avowedly attributed to the weak disaster preparedness cycle which is only focused on response and activated soon after disasters lashes the country. Throughout the year, all authorities enjoy idleness but resort to a sick culture of blame games when disasters take a heavy toll on vulnerable societies. Even in the aftermath of disaster, they seem to be dilly-dallying to carry out rescue, search and recovery operations as well as extend humanitarian assistance to disaster victims. Long-term relocation of disaster victims has long been perceived as a headache by the authorities. The misery experienced by Baglung, Myagdi and Sindhupalchok landslides victims last year is just the tip of the iceberg. Had the responsible agencies of the government put in place policies and programs to enhance the adaptive capabilities of the communities as well as respond on time, such a massive loss of lives, property and psycho-social consequences could have been remarkably reduced.

Regarding this year’ monsoon, the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology has already warned that more 1,800,000 people could be impacted as the country is likely to witness comparatively more than average rainfall. It may impose more challenges on the communities. With this year’s monsoon already in the country and increased vulnerability of hazard-prone societies due to the pandemic crisis, it is utterly imperative we learn lessons from the past disaster experiences and adopt the most possible pragmatic strategies to avert the disaster risks before they turn indelible.

It is essential here that we feel urgency for disaster prevention and preparedness to reduce the potential loss of lives, injuries and property while keeping individuals resilient to withstand the plights in disaster-prone communities sitting in hills and low-lands where rain-hazards are invariably recurrent phenomena. Timely communication, coordinated efforts and dedicated actions among all levels of government agencies, humanitarian agencies, national security apparatus, private partners and communities are always paramount to strengthening life-saving approaches. If acted on time, this certainly helps ease the disaster challenges often experienced by the most vulnerable population of disaster-prone communities—children and elderly citizens including women, patients and differently-abled persons.

In sum, disaster can always be more disastrous than we predict. We must understand that each life is precious. Additionally, it is never wise to remain unprepared for the potential worst any monsoon-triggered disaster can impose on vulnerable societies. Therefore, anticipating the possible consequences of monsoon hazards can help determine the effective action plans that need to be in place before the disasters hit both to prevent and reduce their impacts.

The author is an MPhil Scholar at Nepal Open University.

Leave Comment