Who's my father? Australia law ID's once-secret sperm donors

Agency

August 02, 2018

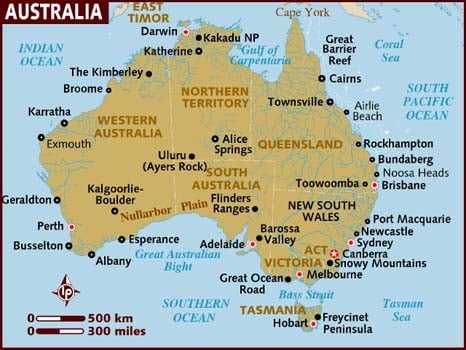

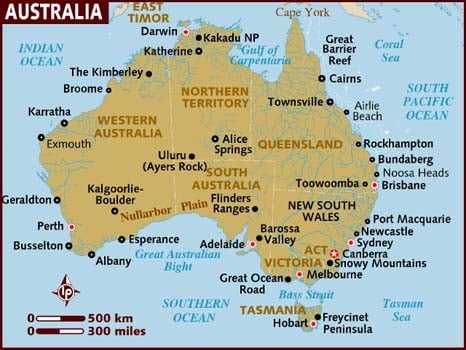

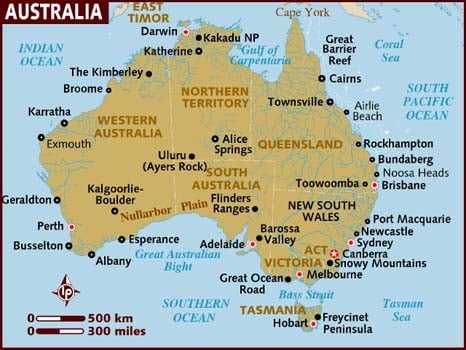

MELBOURNE, Australia – For Peter Peacock, fate arrived in the form of a registered letter.

The letter, at least initially, looked to be a bit of a letdown. Peacock had gone to the post office expecting the delivery of a big, furry aviator jacket he'd ordered online. And so it was with little fanfare that the Australian grandfather and retired cop tore the envelope open as he walked back to his car — at which point he stopped dead in his tracks.

"Dear Mr Peacock," the letter began. "The Victorian Assisted Reproductive Treatment Authority (VARTA) has received an enquiry of a personal nature which may or may not relate to you. The matter concerns a record held in relation to a project you may have assisted with at Prince Henry's Institute."

Prince Henry's? The Melbourne clinic where he'd donated sperm nearly 40 years ago?

There could be only one reason for such a letter, he thought. Someone out there had come to life through his donation.

His mind raced. How on earth was he going to tell everyone? How would he break it to his two grown daughters? And how could this person even know who he was? He had been promised that his donation would be anonymous.

And for decades it was, until a new law in one Australian state retroactively erased the anonymity of sperm and egg donors. Their offspring now have the legal right to know who they are.

Which is why a week after receiving that letter, Peacock found himself staring at a photograph of a woman named Gypsy Diamond, whose face looked so much like his own that he felt an instant and overwhelming connection. He gazed in wonder at her dark, almond-shaped eyes. His eyes.

"God almighty, I looked at it and I thought - 'Bloody hell. I can't deny that girl,'" he says. "She was my child from the start."

---

The walls of VARTA's offices in downtown Melbourne are covered in jigsaw puzzle-shaped notes bearing the hopes of donor-conceived children and the people who helped bring them into the world: "No more secrets." ''May you find your truth."

VARTA is at the epicenter of Victoria state's donor identity law, a piece of legislation dissected and debated for years before finally taking effect in 2017. The agency maintains a register of donors, offspring and their parents, and counsels them through the intricate dynamics involved.

Behind it all was a quest for the truth by people whose lives began in a lab in an era where the sperm and egg donation industry was swathed in secrecy.

The result, for some of those children, was a deep desire to complete the puzzle of their identity. One Australian woman, Kerri Favarato, says the yearning she felt to find her donor was best captured by a Welsh word, "hiraeth." It means, loosely, a homesickness for a place you may have never been, a longing for something you never had.

"It's that sense within you," she says, "that there is something missing."

Recognition of the rights of these children has grown, much like the generally accepted view that adopted children should have the right to know their birth parents. Some countries, including Australia, have now banned anonymous donation. But Victoria is only the second jurisdiction in the world to impose a law retroactively stripping away anonymity without the donor's consent. Switzerland was the first to do so in 2001, but many donor records were destroyed.

The other side, of course, is the missing puzzle pieces themselves: the 2,000-or-so donors who were assured anonymity. Under the law, donors do have the right to demand that their offspring not contact them. Anyone who violates a contact veto can be fined 7,900 Australian dollars ($6,000).

For some, the law sparked fury. Ian Morrison donated sperm in 1976 on the condition that he remain anonymous. That now-broken promise angers him; he has always believed a contract is a contract. Beyond that, though, he worries about whether the children seeking their donors have considered the potential grief for the people who raised them.

"If they're expecting to get two big happy families, that ain't going to happen," he says. "Life's not like that. It's not all going to end up a happy ending."

---

Leave Comment