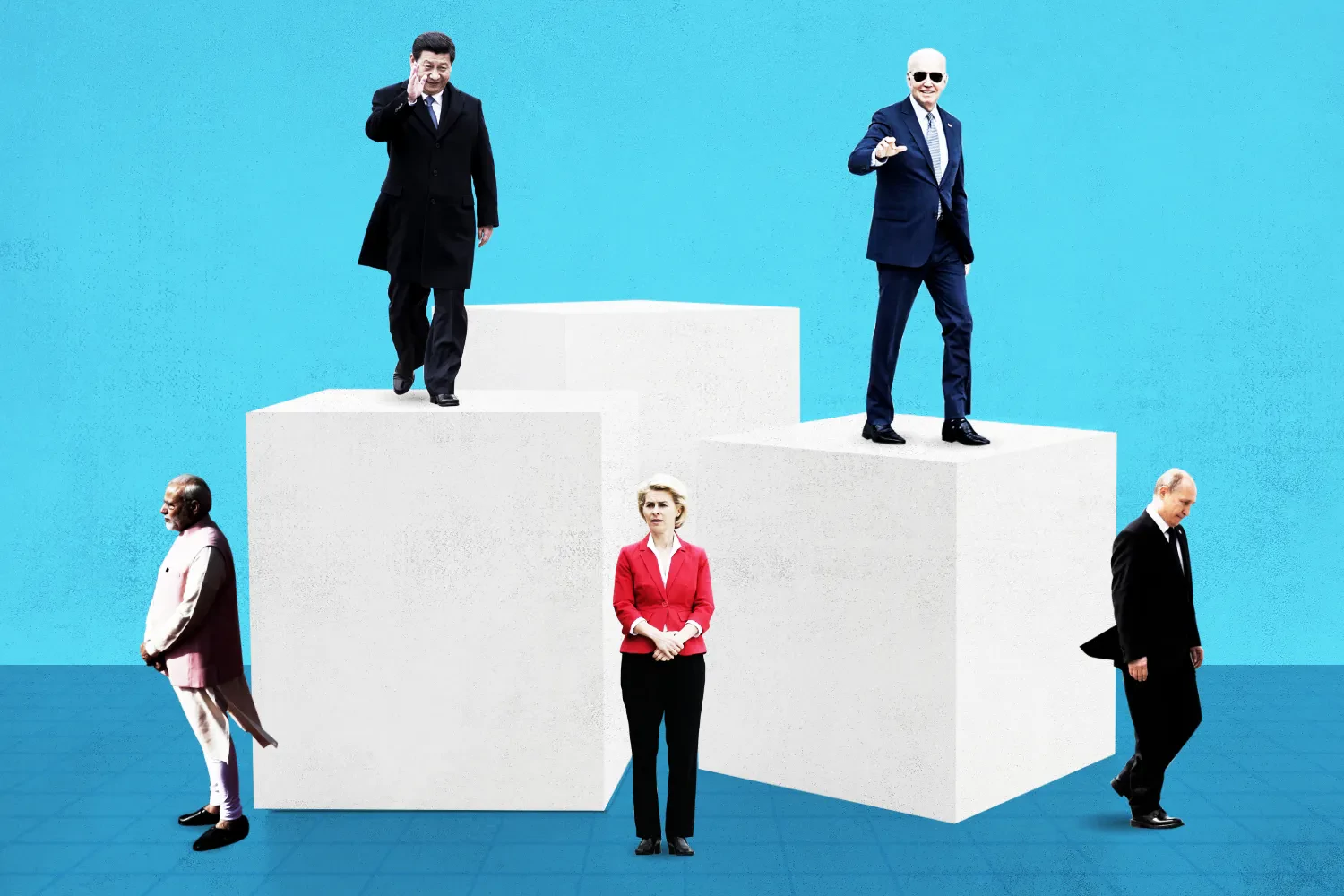

No, the world is not multipolar

Foreign Policy illustration/Getty Images

One of the most persistent arguments put forward by politicians, diplomats, and observers of international politics is that the world is or soon will be multipolar. In recent months, this argument has been made by U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, French President Emmanuel Macron, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and Russian President Vladimir Putin. Josep Borrell, the European Union’s high representative for foreign affairs, argues that that the world has been a system of “complex multipolarity” ever since the 2008 global financial crisis.

The idea is also being popularized in the business world: Morgan Stanley, the investment bank, recently issued a strategy paper for “navigating a multipolar world,” while INSEAD, a respected European business school, is concerned about leadership skills in such a world.

But despite what politicians, pundits, and investment bankers tell us, it is simply a myth that today’s world is anywhere close to multipolar.

The reasons are straightforward. Polarity simply refers to the number of great powers in the international system—and for the world to be multipolar, there have to be three or more such powers. Today, there are only two countries with the economic size, military might, and global leverage to constitute a pole: the United States and China. Other great powers are nowhere in sight, and they won’t be anytime soon. The mere fact that there are rising middle powers and nonaligned countries with large populations and growing economies does not make the world multipolar.

The absence of other poles in the international system is evident if we look at the obvious candidates. In 2021, fast-growing India was the third-largest spender on defense, which is one indicator to measure power. But according to the latest figures from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, its military budget is only one-quarter of China’s. (And China’s numbers may be even higher than commonly believed.) Today, India is still largely concentrated on its own development. It has an undersized foreign service, and its navy—an important yardstick for leverage in the Indo-Pacific—is small compared to China’s, which has launched five times more naval tonnage over the past five years. India may one day be a pole in the system, but that day belongs in the distant future.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan greet each other at the BRICS summit in Johannesburg, South Africa, on July 27, 2018.

Economic wealth is another indicator for the ability to wield power. Japan has the third-largest economy in the world, but according to the latest figures from the International Monetary Fund, its GDP is less than one-quarter of China’s. Germany, India, Britain, and France—the next four largest economies in the world—are even smaller.

Nor is the European Union a third pole, even if that argument has been tirelessly advanced by Macron and many others. European states have varying national interests, and their union is prone to rifts. For all the apparent unity in the European Union’s support for Ukraine, there is simply no unified European defense, security, or foreign policy. There is a reason that Beijing, Moscow, and Washington converse with Paris and Berlin—and rarely seek out Brussels.

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen listen to French President Emmanuel Macron during a meeting in Brussels on June 23, 2022. Ludovic Marin/AFP via Getty Images

Russia is, of course, a potential candidate for great-power status based on its land area, massive natural resources, and huge stockpile of nuclear weapons. The country certainly has an impact beyond its borders—it is waging a major European war and drove Finland and Sweden to join NATO. Nonetheless, with an economy smaller than Italy’s and a military budget equaling only one-quarter of China’s at most, Russia does not qualify as a third pole in the international system. At most, Russia can play a supporting role for China.

A widespread argument among those who believe in multipolarity is the rise of the global south and the shrinking position of the West. However, the presence of old and new middle powers—India, Brazil, Turkey, South Africa, and Saudi Arabia are often named as additions to the roster—does not make the system multipolar, since none of these countries has the economic power, military might, and other forms of influence to be a pole of its own. In other words, these countries lack ability to vie with the United States and China.

And while it is true that the United States’ share of the global economy has been receding, it retains a dominant position, especially when considered together with China. The two great powers account for half of the world’s total defense spending, and their combined GDP roughly equals the 33 next-largest economies added together.

The expansion of the BRICS forum at its summit in Johannesburg last month (previously, the block included only Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) is interpreted as a sign that the multipolar order is here or at least being advanced. However, blocs are too heterogeneous to function as poles—and they can easily fall apart. BRICS is nowhere near a coherent bloc, and while member states may share views on the international economic order, they have widely divergent interests in other areas. In security policy—the strongest indicator of alignment—the two largest members, China and India, are at odds. Indeed, Beijing’s rise is driving New Delhi to align itself more closely with the United States.

So, if the world is not multipolar, why is the multipolarity argument so popular? In addition to the lazy way that it ignores facts and concepts about international relations, three obvious explanations stand out.

First, for many people who advance the idea of multipolarity, it is a normative concept. It is another way of saying—or hoping—that the age of Western dominance is over and that power is or should be diffuse. Guterres regards multipolarity as a way to fix multilateralism and bring equilibrium to the world system. For many European leaders, multipolarity is seen as a preferred alternative to bipolarity, because the former is believed to better enable a world governed by rules, allow for global partnerships with diverse actors, and prevent the emergence of new blocs.

Indeed, the multilateral framework is certainly not working the way it is supposed to, and many in the West view the idea of multipolarity as a fairer system, a better way to revive multilateralism, and an opportunity to repair the growing disconnect with the global south. In other words, belief in a multipolarity that does not exist is part of an entire bouquet of hopes and dreams for the global order.

A second reason that the idea of multipolarity is in vogue is that, after three decades of globalization and relative peace, there is a great deal of reluctance among policymakers, commentators, and academics to accept the realities of an intense, all-encompassing, and polarizing bipolar rivalry between the United States and China. In this regard, belief in multipolarity is a kind of intellectual avoidance—and an expression of the wish that there not be another cold war.

Third, talk about multipolarity is often part of a power play. Beijing and Moscow see multipolarity as a way of curtailing U.S. power and advancing their own position. As far back as 1997, when the United States was the dominant power by far, Russia and China signed the Joint Declaration on a Multipolar World and the Establishment of a New International Order. Even though China is a great power today, it still views the United States as its main challenge; together with Moscow, Beijing uses the idea of multipolarity as a way to flatter the global south and attract it to its cause. Multipolarity has been a central theme of China’s diplomatic charm offensive throughout 2023, while Putin declared at the Russia-Africa summit in July that the leaders in attendance had agreed to promote a multipolar world. Similarly, when leaders of rising middle powers promote the idea of multipolarity—such as Lula in Brazil—it is often an attempt to position their country as a leading nonaligned nation.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Chinese President Xi Jinping, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov pose during the BRICS summit in Johannesburg on Aug. 23. Gianluigi/AFP via Getty Images

One might wonder whether polarity—and widespread misconceptions about it—even matter. The simple answer is that the number of poles in the global order matters greatly, and misconceptions obscure strategic thinking, ultimately leading to the wrong policies. Polarity matters for two very important reasons.

First, states face different degrees of constraint on their behavior in unipolar, bipolar, and multipolar systems, requiring different strategies and policies. For instance, the new German national security strategy, released in June, states that the “international and security environment is becoming more multipolar and less stable.” Multipolar systems are indeed regarded as less stable than unipolar and bipolar systems. In multipolar systems, the great powers build alliances and coalitions in order to avoid one state dominating the others, which can lead to continuous realignments and sudden shifts if a major power changes allegiance. In a bipolar system, the two superpowers mainly balance each other out, and they are never in doubt about who the main rival is. We should, therefore, hope that the German strategy paper is wrong.

Polarity matters for businesses as well. Morgan Stanley and INSEAD are preparing their clients and students for a multipolar world, but pursuing multipolar strategies in a system that remains bipolar could prove to be a costly mistake. This is because trade and investment flows can be very different depending on the number of poles. In bipolar systems, the two great powers will be very concerned about relative gains, leading to a more polarized and divided economic order. Each type of order comes with different geopolitical risks, and a mistaken strategy on where a company should build its next factory can be very costly.

Second, advocating a multipolar world when it is clearly bipolar could give the wrong signals to friends and foes alike. The international stir caused by Macron’s statements during his visit to China in April illustrates the point. In an interview on his plane during the flight back to Europe, Macron reportedly emphasized the importance for Europe to become a third superpower. Macron’s willingness to muse about multipolarity did not go down well with French allies in Washington and Europe. His Chinese hosts appeared delighted, but if they confuse Macron’s reflections about multipolarity with French and European willingness to support Beijing in the U.S.-China rivalry, they may have gotten the wrong signals.

A multipolar system may be less overtly polarized than a world with two adversarial superpowers, but it would not necessarily lead to a better world. Instead of being a quick fix for multilateralism, it could just as well lead to further regionalization. Rather than wishing for multipolarity and spending energy on a system that does not exist, a more effective strategy would search for better solutions and platforms for dialogue within the existing bipolar system.

In the long term, the world may indeed become multipolar, with India being the most obvious candidate to join the ranks of the United States and China. Nevertheless, that day is still far off. We will be living in a bipolar world for the foreseeable future—and strategy and policy should be designed accordingly.

(Jo Inge Bekkevold is a senior China fellow at the Norwegian Institute for Defence Studies and a former Norwegian diplomat.)

Read the original article here.

Leave Comment