Our Social Fabric is Torn, But the Poll Mandate Has Laid the Ground For India's ‘Rehumanisation’

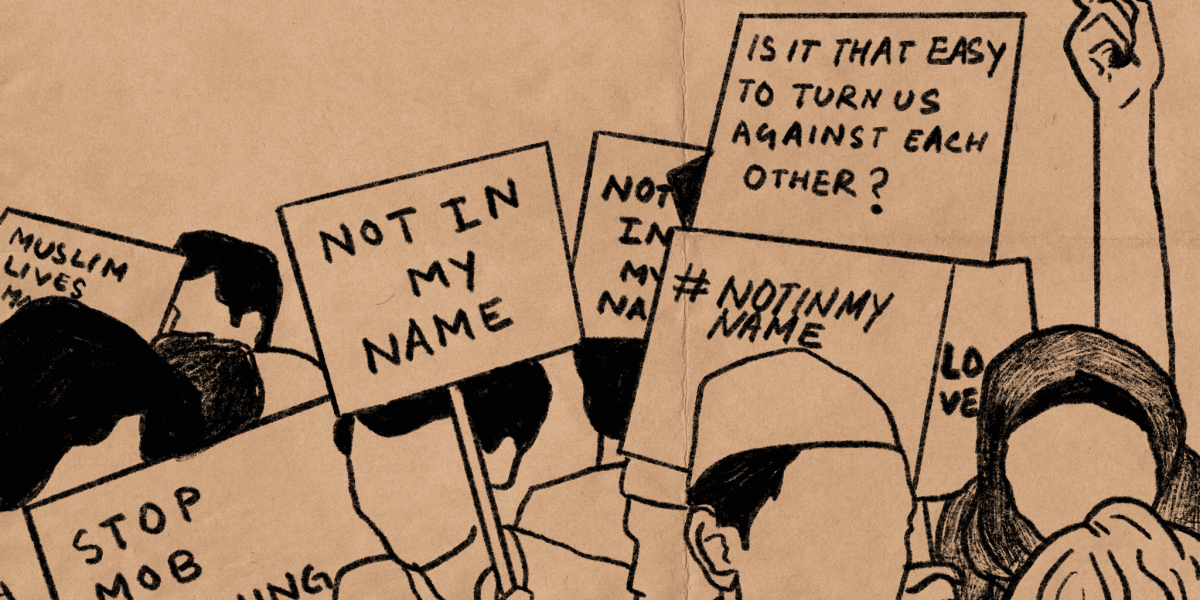

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

Apoorvanand

Redemocratisation and resecularisation: these are two tasks that emerge from the mandate of the 18th Lok Sabha elections. But to make them possible, what is most needed is the rehumanisation of India as a state and as a society.

One realises how difficult this is when trying to type this word – the computer autocorrects it to dehumanisation.

So the journey has to be from dehumanisation to rehumanisation.

Before we talk about these two things, it needs to be said that the election mandate is not only about the ruling formation, but also about the opposition. In fact, this is one of those rare elections in which the opposition, with its fewer numbers, is being seen as the victor.

This is because of the near-total unanimity that was created in the minds of the public by and through media that it was Narendra Modi, the monarch, who was the destiny of the Indian people, that Indian people did not have any choice but to vote a monarch into power to lead them into a promised future called viksit Bharat.

The present generations have only one task: to keep running towards that future and not expect their present-day life to be bettered. They had to be transformed from rights-bearing people into duty-bound subjects.

Through this mandate, his monarchical ambition has clearly been punctured. But that alone will not change the man. This time, he went naked to the town, brazenly displaying who he was: a dyed-in-the-wool anti-Muslim fascist, committed to turning India into a land where Muslims and others should not expect the state to accord them equality of opportunity and extend its helping hand when they need it.

He put Hindu interests against Muslim interests and asked his constituents to vote him into power to safeguard their Hindu interests, from mangalsutra to the Ram Mandir. He and his party have been giving one message to the Hindus: it was not enough for them to be docile subjects of the monarch, they had to be Muslim haters or Muslim-sceptics.

He and the BJP clearly defined the relationship between Hindus and Muslims: Hindus have to meet Muslims not with a handshake but with a fist.

Modi and his party have been dehumanising Muslims by turning them into non-people, unwanted infiltrators. People without rights. Without the expectation of justice.

But it is also dehumanising Hindus by turning them into people who cannot live with differences, who are hateful towards and jealous of others, who cannot believe in the possibility of a shared country and shared humanity. From colonies and apartments to the nation: it has to be a Hindu-only land.

It really demeaned Hindus. They have been traditionally seen by the world as a people tolerant of diversity and largely accommodative. This is despite their lives being segregated and divided along caste lines. But one can accept that they did not feel that they were the chosen people. The absence of a central text defining Hinduism was seen as proof that it was essentially plural and Hindus were relaxed with different ways of life.

The last ten years seem to have changed Hindus. They are now seen as people who cannot tolerate difference, who rejoice in the plight of others, especially Muslims and Christians.

A fresh mandate to the BJP for an absolute majority would have meant that Hindus would further descend into this pit of hatred and violence. But the mandate that we have now says that there is a possibility to turn back.

In Chandigarh, going from the railway station to Mullanpur, I had a 45-minute-long chat with the auto driver. He is from Bahraich in Uttar Pradesh. “Sabko milakar chalna chahiye [one should take everyone along with them],” he said. He meant all castes. After a pause, I added, yes, including Muslims.

I did not hear back from him. Maybe my voice was lost in the din of the traffic. But this is the challenge. To make people hear this plea. To stitch back a torn social fabric. It will take more than one election or elections to do that.

We do not expect the BJP to retreat from this path. It is evident from the speeches of leaders like Himanta Biswa Sarma, who blamed one particular religion for the poor performance of the BJP in his region. And the frenzied online trolling of the Hindus of Uttar Pradesh for their ungratefulness.

One can see that there is now a well-oiled machinery with the BJP, which works overtime to intimidate and shame those Hindus who refuse to be hateful by calling them cowards, ungrateful, betrayers, etc. To face it, stand up to it, is not easy.

This is what defines the BJP and its politics. So, this is the task of the opposition: to go to the people and explain to them the meaning of the mandate they themselves have generated in this election.

There could be umpteen reasons, local factors and other micro-causes for the BJP’s defeat. But what this defeat and pushing back means is not yet clear to the people, as I could gather from my conversation with the auto driver.

He was, as are others, harassed by the wandering cattle destroying their crops, but is he also upset with the bulldozing of the house of a Muslim? Does he feel bad that his religious processions are used to insult and humiliate Muslims? That their boys are now being recruited as foot soldiers of the hate armies that have been mobilised in these last ten years? That their spiritual gurus are actually hate preachers?

Mastering a caste equation that clicked this time is not a permanent thing the opposition can rely on. Krishna Pratap Singh, the astute observer of the social and political life of Uttar Pradesh, rightly warns that the gains that this potential ‘Mandal 2’ moment has made can be lost if the opposition again lapses into complacency about its permanence as it had done after Mandal 1. You talk to people in Uttar Pradesh and hear them doubting if the gains will hold till the assembly elections.

So, it has to go beyond the instrumentality of elections. We are told that Yadavs understood the compulsion of other castes being given a greater number of seats, but will they be ready to ‘make the sacrifice’ even in the next elections? Why did INDIA succeed in UP but could not do so in Bihar, given the nearly similar caste distribution?

Social coalitions have to be made and continuously expanded. Justice for one cannot be at the cost of others. Who will take this message to the people? There was one Gandhi who tirelessly did it even when the main task seemed to be to free India of British domination.

Which India is seeking freedom, was the question Gandhi posed. What was the quality of that idea of India which claimed that it had the right to remain independent? What does being independent mean? Which nationalism does this independence espouse?

The moral authority of Jawaharlal Nehru ensured that the Gandhi era continued for a while, despite the hatred and violence generated by the partition of India. People and Hindus too took pride in the fact that they believed in togetherness and diversity. They could not be prisoners of their imaginations of the past.

This was what our leaders like Nehru meant by secularism: the nation belongs to all and your greater numbers or population does not make you the first people of the nation and does not give you authority to force others with a lesser population to follow your way of life. No way of life can claim to be the nation’s only way of life.

There was no one who was ready to stake their honour and position to safeguard this idea after Nehru. No one thought that what we had achieved was tentative, unstable and had to be reaffirmed again and again.

Nehru always welcomed elections as opportunities for people to be educated about ideas that were new to everyone. It was a careful nurturing and cultivation of these ideas of togetherness, sharing and thinking beyond your own self, your own clan and new solidarities on the principles of maitri as Ambedkar proposed.

Only this maitri could bring democracy and secularism together. Otherwise, the democratic argument could always ask secularism to give way as we saw in 1966, 1967, 1977, the 1980s and even now. It is argued that for the sake of democracy, one can compromise on secularism.

The electorate might not have thought about it while voting against the BJP. They would have voted against the arrogance of Modi or the BJP, or to punish the BJP for their miserable lives, or to see their identity represented. But the larger meaning of the mandate they have crafted half-knowingly has created a space where opposition leaders can talk about a shared collectivity.

There is less bitterness on the ground, the leaders have gained confidence through the mandate to talk boldly about the necessity of love among people, about this difficult emotion of love.

Only this will change what is now the default setting: when it will be possible that if someone writes ‘dehumanise’, their computer will get correct it automatically to ‘rehumanise’.

(Apoorvanand teaches Hindi at Delhi University.)

- The Wire

Leave Comment